Over the past several years, Deking Screw Products has specialized in Swiss-type machining — a big shift from its former operations. It’s also recently been handed off from the second generation of family ownership to the third. Photo Credit: Deking Screw Products

“I was always afraid I was going to let my dad down.”

The year was 2008 and production had slowed to a crawl. Geno DeVandry had been working for the family business since the age of 14, following in the footsteps of his father, Eugene, who had dropped out of school after sixth grade in order to help operate screw machines and make munitions for the war effort in the early 1940s. Now Geno was in charge as the second-generation owner of Deking Screw Products, a machine shop located outside of Burbank, California that Geno’s dad started in 1962.

Featured Content

And now the business was in trouble.

Business at Deking first began to slow down in the early 2000s when foreign competition began undercutting sales. Employees who had worked at the shop for decades were worried about their jobs, though no one was more worried than Geno. Several of the older employees had been hired decades ago by his father and were considered to be family. It was true that there wasn’t enough work to keep them busy, but you can’t let go of family.

“The big fear I had in my life while growing up and running the business,” Geno says, “was that I was going to let my dad down. You know, fail. It's a scary feeling to think you failed. And there were times I thought, man, I'm not going to make it. And truthfully, one of the big differences between what Dave and I are doing, is that David's got all this data, and he sees things way ahead of time. Me, I ran things by the seat of my pants because I didn't have a business degree. I grew up in the shop and my dad didn't prepare me because he didn't have that either.”

It was at about this time during my interview with Geno that his son, David DeVandry, burst into the room.

“Can I borrow your keys? My car's not here and I have to go pick up...”

“You're interrupting our conversation,” Geno interrupted back.

“I'm sorry. I won't interrupt anymore,” David said, disappearing with his dad’s car keys.

The exchange between Geno and David was a commonplace family moment: A jokingly annoyed dad lends his son the car. But the moment was also a window into the family dynamic at a machine shop that recently passed from second-generation ownership, Geno, to the third, David. At a time when succession planning for machine shops is top-of-mind for retirement-aged shop owners, a peek inside Deking Screw Products offers more than just a generational portrait of a family machine shop. What recently took place at Deking was a transition not only into a new operations plan for the company, but a transition into a new production technology using Swiss screw machines.

The DeVandrys’ story is about how one family navigated those changes, learned from its own mistakes, and pushed beyond the interpersonal family dynamics for the greater good of the shop and its employees.

“I Need You to Step Up”

Five years after Eugene DeVandry and his business partner founded Deking Screw Products, the company relocated to an industrial section outside of Burbank, California, a part of town dotted with old prefab Quonset huts that were popularized during WWII. The shop floor housed a half-dozen Acme multi-spindle machines that Eugene and his son Geno operated in day-long shifts — setting up a job, running it all day, removing it, setting up the next job — back and forth throughout each week.

This work continued until the day that Geno’s father shared his tragic news: A triple-bypass surgery was his father’s only option to survive what had been a severe and ongoing heart condition. But during this time Eugene also shared with Geno — in a roundabout way — his hopes for the family business:

“He came to me one day and he said, ‘I need you to step up,’” Geno recalls. When the family located a doctor who was willing to do this triple bypass, Eugene took Geno to the bank. “He put me on the signature card so I could sign payroll and then brought me back to the shop. He showed me one of his work estimates and showed me how to adjust that quote for different quantities. I was 18 or 19 years old. I just out of high school going to college, but I stopped school because I was too busy there. My dad’s business was everything to him, and I knew that the only thing I could really do for him was to take care of it.”

Still just a teenager, Geno took over day-to-day operations at Deking Screw Products in the mid-1970s. The shop was running seven Acme multi-spindle machines and employed a handful of workers who had been hired by Eugene years before. Geno was single, young, and logging 70-hour work weeks, leaning on the shop’s experienced staff to learn the ropes. The work paid off.

“Fortunately I had some good people around me,” Geno says. “I'd asked them a lot of questions. And then after the first month, we had the best sales we’d ever had. It was unbelievable.”

The second month was better than the first, and the third month topped them both. Eugene’s father moved back to the family’s home state of Tennessee, leaving Geno fully in charge of Deking Screw. Geno made changes slowly, beginning with the purchase of a computer system in the early 1980s, followed by CNC lathes and mills. Geno’s stepbrother joined him to help run the business, which by that time was attracting mostly defense and aerospace work. By the late-’90s, Deking Screw employed more than 40 people, some of whom had been with the company since the 1960s. If you measured Deking’s profitability by subtracting accounts payables from receivables, the business was doing fine.

Then the 2000s hit, and things changed. By that time Geno had five children of his own, including his youngest, David, who studied engineering in college but switched his focus to become a math tutor for an education startup company. Meanwhile, Deking was still running the Acme multi-spindles and maintained most of its employees despite the steep loss of work. But when the Great Recession struck in 2008, business conditions went from bad to catastrophic. Soon, Geno had no choice but to let nearly all of Deking’s 45 employees go. Only the fact that the shop carried no debt kept it alive.

One and Done

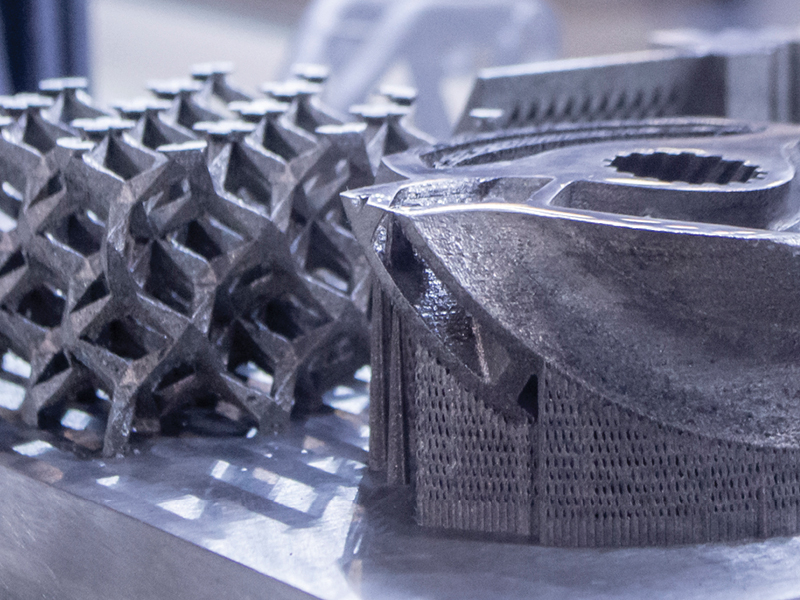

By 2015, Jouni Levenan was one of the top Swiss-type machining experts employed as a West Coast sales rep for Marubeni Citizen-Cincom. His daughter played soccer for one of the several teams that Geno DeVandry coached throughout the 1990s and 2000s, and the two men often talked after the games about business and their latest discoveries in CNC machining. One day Geno showed Jouni a complex part that had been machined recently at Deking — a part that Geno was particularly proud of. But Jouni was unimpressed.

“He said, ‘I could run that one-and-done on a Swiss,’ ” Geno says. “And I said ‘Are you kidding? No way. Not this part.’ We had about five operations for this part.” The conversation stuck in his mind that night, and the next day Geno seized an opportunity.

“I called Jouni and left him a message to call me back,” Geno says. “Two hours later he calls and I say, ‘Are you ready to start a business?’ And he said, ‘Heck yeah!’ This was the day before I was going to put a down payment on new EDM machine. So I canceled the EDM and bought our first Swiss screw machine.” As soon as the machine arrived, Geno and Jouni began making parts, effectively launching Deking Screw Products 2.0 — a precision part manufacturer with a new focus on Swiss-type machining. Jouni left his job with Citizen, and Geno went from literally praying that he’d make payroll each week to growing the business through Swiss machining operations.

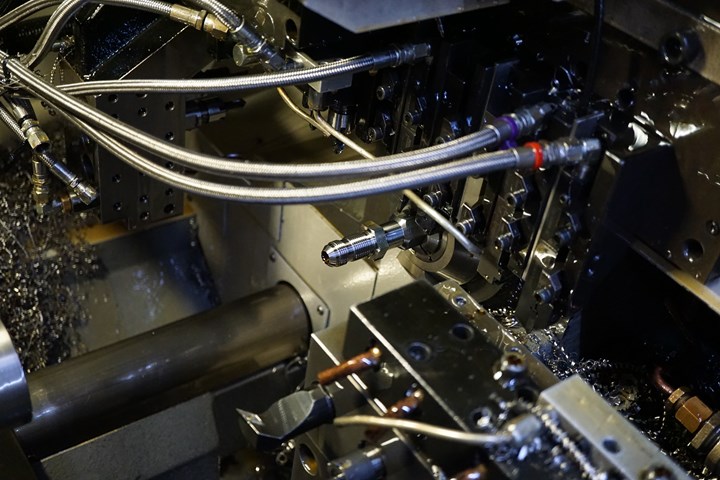

A look inside one of Deking Screw Products’ Citizen Swiss-type machines. The company recently purchased it tenth. Photo Credit: Deking Screw Products

“When the Swiss machine came in, things started changing,” Geno says. He’d been able to rehire some of the longstanding employees he had to let go during the downturn. “And then I started thinking about how David had worked here as a kid working on the old Acme screw machines that were now 50 years old,” he says. “David grew up in that environment. So when the shop really got going again, I told him to come in and take a look.”

By that time, Dave DeVandry had determined that he enjoyed the business-operations side of his math tutoring work more than anything — managing the company’s education centers, opening new ones, implementing data collection systems, tracking progress as new centers came online. It’s why the news from his dad that Deking Screw Products had launched a new side of the business drew him back, not only to a place that was familiar, but to one that he knew could use the skills he’d acquired over the last couple of years. For the next two weeks after talking to Geno, David visited the shop each day, thinking about whether it was the path he wanted his future to take.

He decided it was. And so David returned to Deking, and it did not go well.

Well...

Not at first, anyway.

While the Swiss side of the shop was taking off, David found that other aspects of the business were running on outdated technology. He determined that the shop was only utlizing 10 or 15 percent of the ERP system’s capabilities. It was still printing and faxing quotes and dealing with RFQs one vendor at a time. (“My dad's never seen a filing cabinet that he didn't want to buy,” David jokes.) But the most pressing issue was with the Acme side of the business. More and more work was being moved to the Swiss-type machines, and now overhead with the Acme division was hurting the business.

The swiftness with which these conversations took place between David and Geno — not to mention the fact that they are father and son — created tension. The two DeVandry generations thought the other was moving too fast or too slow. Predictably, the pressure came to a head. One day David wrote a letter to Geno, stating that unless there a few changes, he would be moving on.

“My dad was raised on these Acmes,” David says. “The Acmes paid for everything in our family. And we’ve had multiple employees in the Acme division that have been working with us for over 40 years. So I understood that when I talked about closing the department down, for him that means that he is going to have to lay off employees that are like family. And one thing I can tell you about my dad is that he's always taking care of his employees. He would rather be the guy being taken advantage of than the other way around.”

David’s letter to Geno was as objective and unemotional as he could be. It presented raw numbers that were impossible to ignore. But the letter also reminded Geno of something; it reminded him of a very similar exchange he had with father more than 40 years before.

“The biggest problem David and I had in the beginning was that he wanted to change everything overnight,” Geno says. “And I wanted to take things one at a time. But then I remembered that I did the same thing to my dad. I did the same thing. When I worked in the shop when I was younger, people literally didn’t know I was his son. I was an employee. He was tough. But one day I told him, ‘You know what, I'm leaving in two weeks. You’ve got two weeks’ notice and then I'm going to get another job. And during those two weeks, he kept talking about our future. And when it got to the end of those two weeks, he said — and I don’t think my dad ever said this to anybody ever in his life — he said, ‘Son, don't you know I need you here?’ ”

“That is the same situation with David,” Geno says. “I need him. I want the shop to keep going because I look at this place like an heirloom. My dad passed it on to me, I passed it on to him. And he’s got two boys and I’'ve got grandkids and maybe someday it will be passed on to them. But you look at those things and sometimes think, How long can this go on? Three generations? That’s not easy to do.”

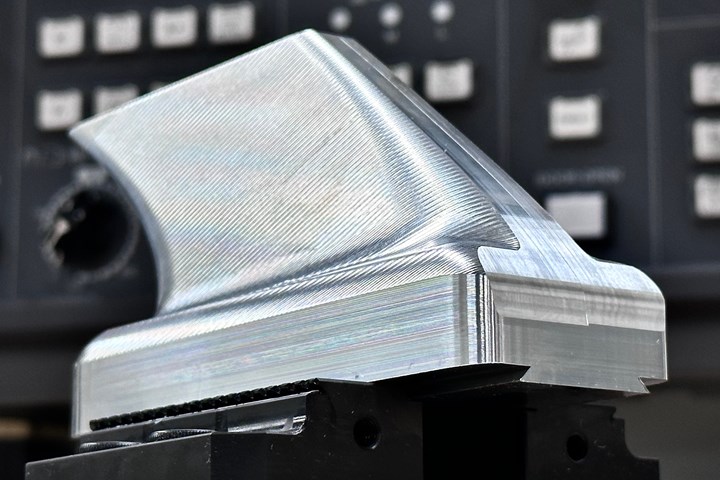

Today, Deking Screw Products operates 10 Swiss-type machines, including six Cincom A20s, two A32s, and two L12 VIIs. The shop has been fully digitalized, revamped its production flow through the ERP system, and achieved AS9100 certification. It continues under David and Jouni’s leadership, with Geno coming and going to assist when he pleases, which, when I talked to him, was just in time for David to borrow his car.

“David basically told me that he couldn't continue with the way things are going,” Geno says, remembering the letter. “He needed more from me. And I'm going to tell you, that really hurt. I remember saying to him, ‘Just be patient. It's not that I don't want you to run this place, I just want you to slow down a little bit.’

Geno DeVandry, David DeVandry, and Jouni Levenan.

But I had to remind myself that when I took over for my dad, he got out of the way. He let me make my mistakes. David has made some dramatic changes in the shop, and right now they are set and ready for this next surge in business. I think we’re going to see it, and I’m excited about the future. We’ve got all the certifications in place, we’ve got people trained and learning new jobs. They’re in a great position for the future.”

Editor’s Note: You can hear more of Geno and David DaVandry’s story and listen to their interviews on Modern Machine Shop’s new podcast, “Made in the USA.” Check out the show’s website, or visit your favorite podcast platform to subscribe now.

RELATED CONTENT

-

Modern Machine Shop and ProShop ERP Announce New Conference

The Machine Shop Ownership Change Conference focuses on setting up shops to succeed during transition. The digital event provides shop owners information to improve their company value, reduce the risk of their business transition and increase their chance of success.

-

RobbJack Corporation Names New President

Over his 26 years at RobbJack, Michael MacArthur has developed a reputation for building relationships and providing innovative solutions to meet customer challenges.

-

Stars Slowly Align for Small Shop Merger

RPM Tool’s seemingly overnight expansion from a five-person machine shop to an almost 30-employee production business involved over a year and a half of planning.

.1692800306885.png)

.1687801407690.png)