Peter Zelinski: Welcome to Made in the USA, the podcast from Modern Machine Shop Magazine exploring some of the biggest ideas shaping American manufacturing. I’m Peter Zelinski.

Brent Donaldson: I’m Brent Donaldson. So Pete, I think it’s safe to say that out of all of the topics we’ve covered so far — the recent history of manufacturing, automation, the supply chain, our misperceptions about how we view manufacturing careers and education and training — out of all of that, the topic we’re about to get into is the most personal and the most immediate, when it comes to what is looming on the horizon for independently owned machine shops.

Featured Content

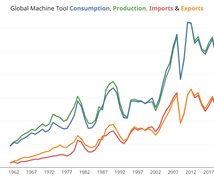

We’re talking about ownership change taking place within manufacturing right now — a phenomenon that is bearing down on the industry as baby boomers reach retirement age.

Pete: The last baby boomer was born in 1964. That means, by 2030, every single member of the baby boomer generation will be over 65 years old. Think about that. This is a generation of roughly 73 million people! By 2030, people over the age of 65 will account for 20% of the entire U.S. population. When you couple this with the sea change in machine shop ownership and leadership that our writers on Modern Machine Shop Magazine have reported on recently, the conclusion is hard to miss: we are entering a season of fundamental change for machine shops and for manufacturing in this country.

The stories about this phenomenon that we’ve written about recently have taken several shapes, from formal acquisitions and mergers, to generational planning for family-owned shops — or the lack of it — to instances where the best option might be to put the shop and all of its equipment up for auction.

As we’re about to hear, sometimes these stories can be very personal. Sometimes, they can teach us lessons that go much deeper than the transactional nature of a typical business acquisition story.

Brent: So let’s meet Geno and David DeVandry, the father and son team who represent the second and third generation of DeVandries to run Deking Screw Products, a high-precision, swiss-type machine shop near Burbank, California.

Pictured left to right: Geno DeVandry, David DeVandry and Jounni Levenan. Photo Credit: Deking Screw Products

We’re going to step back a bit to the year 2008 — the onset of the Great Recession — a year when production slowed to a crawl at the shop.

Geno had been working for the family business since he was 14 years old, following in the footsteps of his father Eugene, who had himself dropped out of school after sixth grade in order to help operate screw machines and make munitions for the war effort in the 1940s. Now Geno was in charge, it’s 2008, he’s the second-generation owner of Deking Screw Products.

And now the business, well--

David DeVandry: Everything kind of went to crap.

Brent: The recession in 2008 was a low-water mark for a business that had begun to sink during the early 2000s — a time when foreign competition began undercutting sales. Here’s how Geno puts it:

Geno DeVandry: My guys were bringing in stuff from the 99-cent store, like a brass hose nozzle, a two-piece hose nozzle. And they bought it for 99 cents. And we started looking at how they made that. I said, “We couldn't buy the material for the price they were selling it! Here we are, selling our brass chips to China and they're bringing it back over here cheaper than we could buy the material.” So we knew we were in trouble.

Pete: During this time, the employees who had worked at the shop for decades were increasingly — and it turns out, justifiably — worried about their jobs, although no one was more worried than Geno. At its height prior to 2008, Deking employed almost 50 people, some of whom had been hired decades ago by Geno’s father. These employees were considered family. Maybe it was true that there wasn’t enough work to keep them busy, but to Geno, who is gregarious and loyal, you can’t let go of family.

Geno: I think the big fear I had my life, running the business, I always afraid I was going let my dad down, fail. It's a scary feeling to think you failed. And there were some times that I’d think, “man, I'm not going to make it.” It was scary at times and it’d be up and down. There's always cycles in this business. And truthfully, one of the big differences between what David and I are doing, I mean, David's got all this data going on, and he sees things way ahead of time, he knows what's going on and it impresses the heck out of me. Me, I ran things by the seat of my pants because I didn't have a business degree. I grew up in the shop and my dad didn't prepare me. He didn't have that either.

Brent: Just as a side note here: it was at this first emotional point in the conversation when his son David burst into the room.

Geno: My son's asking me something.

David: Can I borrow the keys? My car's gone and I gotta go...

Geno: Oh here we go, you are interrupting our conversation.

David: Oh, so sorry. I won't interrupt anymore. See you!

Brent: That exchange between Geno and David will sound familiar to a lot of parents: Dad acts annoyed when his kid asked to borrow the car. But the relationship between the father and son during this time, when ownership of the family business was transitioning from Geno to David — that period was intense.

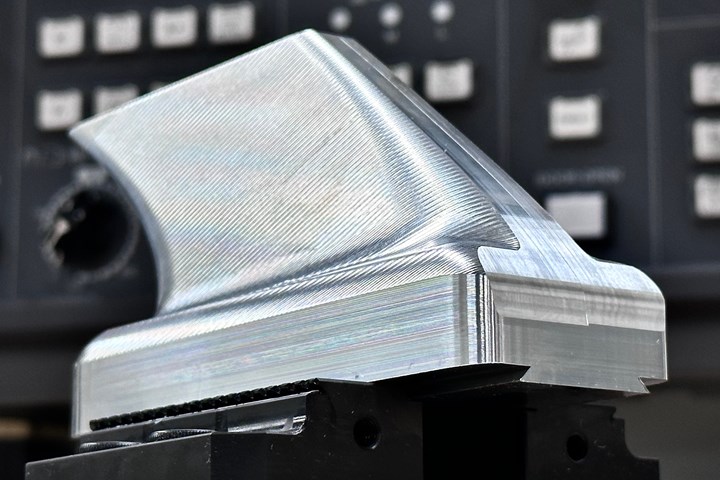

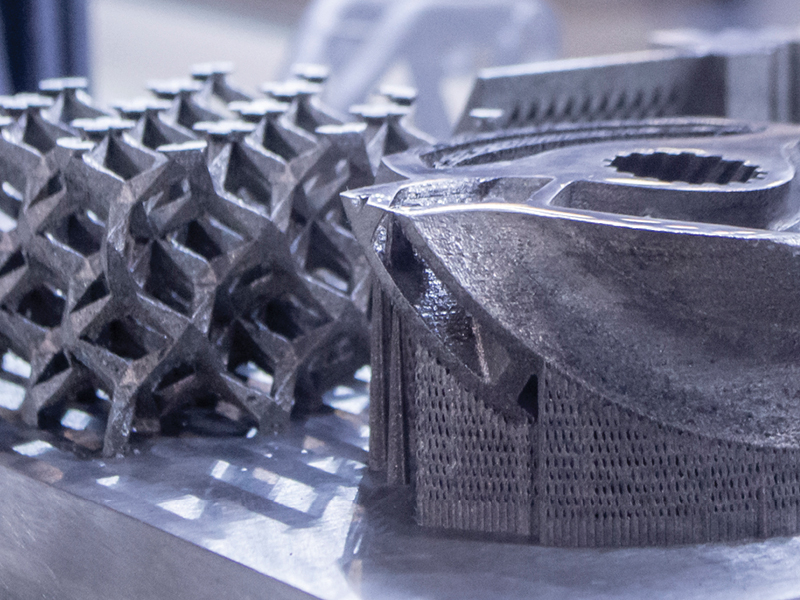

The transition at Deking was not only into new leadership and a new operations plan for the company, but also a transition into a new production technology using a type of machine tool called computer numerical controlled (or CNC) Swiss-type machines — machines that are very different. They are programmable, rather than mechanical, but also much more efficient than the old Acme-brand machines that Geno utilized to run the shop.

The DeVandrys’ story is about how one family navigated this transition: how Geno and David learned from their mistakes and pushed beyond their differences for the greater good of the shop and its employees.

Pete: So let’s start at the beginning, 1967, five years after Eugene DeVandry and his business partner founded Deking Screw Products. The partners had just relocated to an industrial section outside of Burbank, California, a part of town dotted with old prefab Quonset huts that were popularized during WWII. The shop floor housed a half-dozen Acme multi-spindle machine tools that Eugene and his son operated in day-long shifts — setting up a job, running it all day, removing it, setting up the next job — back and forth throughout each week.

This work continued until the day that Geno’s father shared a piece of tragic news: Eugene had been suffering from a heart condition that had worsened to the point that his only option to survive was a triple-bypass surgery. When Eugene broke the news to Geno, he also shared with him — in a roundabout way — his hopes for the family business.

Geno: My dad came to me and said one day, “You know, I need you to step up. I'm gonna have to have this surgery.” He didn't tell me how serious it was until I found out later. But he had a triple bypass. He was losing the blood in his feet, his toes were turning black and they thought they were going to have to amputate, all kinds of things. They finally found a doctor who was willing to do this triple bypass. And he came to me, he says, “Let's go to the bank,” and he put me on the signature card so I could sign checks. He brought me back to the shop, took one of his estimates and showed me how to adjust that quote for different quantities. He didn't show me how to quote, he just showed me how to adjust his quote. And then he showed me how to calculate material, so I’d know how much material to buy.

That was my lesson, and the next day, my dad went into surgery. I was a young kid, I was probably 18, 19 years old. I was just out of high school, going to college, but I stopped school because I was too busy there. And I knew the only thing I could do for my dad, because his business was everything to him, was to take care of it. So I worked my tail off.

Brent: Still just a teenager, Geno took over day-to-day operations at Deking Screw Products in the mid-1970s. The shop was running seven Acme multi-spindle machines and employed a handful of workers who had been hired by Eugene years before. Geno was logging 70 hours every week, leaning on the shop’s experienced staff to learn the ropes. That hard work paid off.

Geno: I wasn't married, so it didn't make a difference. I was just a young kid going to work. And fortunately for me, I had some good men around me who were very helpful. I leaned on them a lot. I asked them a lot of questions and got their help. So the first month, we had the best sales we ever had, it was unbelievable. The second month was better than that. And the third month was better than that one.

So when my dad came back, he said, “Well, you don't need me here.” Pretty much retired. And that was a big mistake, because that put a lot on me. I mean, I was scared. And I remember probably within less than a year, he moved back to Tennessee. And I remember he moved. It was a scariest feeling, because I had no one to lean on, I thought.

Pete: Geno’s stepbrother joined him to help run the business, which by that time was attracting mostly defense and aerospace work. By the late 1990’s, Deking Screw employed more than 40 people, some of whom had been with the company since the 1960’s. If you measured Deking’s profitability by subtracting accounts payable from receivables, the business was doing fine.

Then the 2000s hit, and things changed. By that time Geno had five children of his own, including his youngest, David, who studied engineering in college but switched his focus to become a math tutor for an education startup company. Meanwhile, Deking was still running the Acme multi-spindles, and kept most of its employees on the payroll despite the steep loss of work. But when the Great Recession struck in 2008, business conditions went from bad to catastrophic. Soon, Geno had no choice but to let nearly all of Deking’s 43 employees go. Only the fact that the shop carried no debt kept it alive.

Brent: Geno kept the business afloat this way for several years. By 2015, meanwhile, not far from Geno’s shop, a man named Jouni Levenan was a leading CNC Swiss-type machining expert, employed as a west coast sales rep for Marubeni Citizen-Cincom, a machine tool supplier known for this type of machine. Jouni’s daughter played soccer for one of the several teams that Geno DeVandry coached throughout the 1990s and 2000s, and Jouni and Geno often talked after those games about business and their latest experiences in CNC or automatic machining. Literal shop talk.

One day, Geno showed Jouni a complex part that had been machined recently at Deking — a part that Geno was particularly proud of.

Jouni was unimpressed.

Geno: One day he comes out in the shop with me, I'm showing him a part that I'm really proud of. And he says, “You know, you can run that on a Swiss.” I said, “No way. Not this part.” “Oh, yeah, you could run that finished on the Swiss.” I thought, are you kidding? Because we had about five operations on this part.

Pete: The conversation stuck with Geno that night, and the next day he seized an opportunity.

Geno: The day before, I put a down payment on a new EDM machine. And I told Jouni, I got him to sign, I said, “Jouni, give me a call.” So about two hours late, he calls me, I said, “Hey, are you ready to start this business? He said, heck, yeah.”

I cancelled the EDM machine, and I bought our first Swiss screw machine.

When the Swiss machine came in, things started changing.

David: At that point, you know, my interest started perking up more like, “Oh, hey, we have a future here now.”

Pete: This is David DeVandry, Geno’s son.

David: That's when we, my dad and I, started talking about me maybe coming back in and potentially taking over.

Brent: By that time in 2016, David DeVandry had determined that he enjoyed the business operations-side of his math tutoring work more than anything — managing the company’s education centers, opening new ones, implementing data collection systems and so on.

This is why the news from his dad that Deking Screw Products had launched a new side of the business drew him back. For the next two weeks after talking to his dad, David visited the shop each day, thinking about whether it was the path he wanted his future to take.

He decided it was. And so David returned to the family business, and it did not go well.

David: Before I actually made the full switch, I was coming in a few hours every week and just kind of seeing how things are running, seeing if it's something I wanted to do. And at that point, I noticed a few things that I didn't really necessarily like, but again, I wasn't really into the nitty-gritty yet, so I didn't know really where things are at. It wasn't until probably about two or three months into it where I was like okay, there are some major problems we’re going to have to fix here.

I think at that point, too, you know, the systems were set as they were, and they weren't really budging. We had a folder system where every time we had a cert come in, whether they were material certs or plating, it went in the job folder. The problem with that is, if you send different lots off to plating, then you have two different heat lots, and you can't put the same certs in the same folder because then you don't know what heat lot — you lose your heat traceability. So that's one issue that in the beginning, we had to fix pretty quickly.

My dad is a bit of a micromanager. He likes to be on the shop floor, and he might disrupt things by — well, I’ve got a story for you. We had some parts for which we had just set up an MRB cabinet. And I talked to my inspection room manager, I said, “Okay, we knew what the MRB is for, if we wanted to lock parts in there to make sure that if there's a problem with the part that it wasn't being pushed on the shop floor anywhere.” So, we had some parts that we were waiting on a deviation from a customer for. And I told the inspection manager, I said, “Hey, can you put these boxes in the MRB closet?” And as I was talking to my dad immediately comes over? And he says, “No, you don't want to do that. You can put them over here. Well, I'm sure that deviation will be approved.” And I said, “Dad!”

We actually got into a huge fight at that point. I gave him this glare, he knew I was mad at him. And then we ended up being in a big fight. Because he kind of overstepped me, right in front of — I was actually managing the inspection room manager as well. And I said, “It's not a matter of whether or not this deviation is going to be approved. I'm sure it's going to get approved, but the system needs to be followed, because it needs to be followed every single time.”

So he would do these things where he would come in and micromanage and overstep things. I understand why he did it based on how he was running his business. I think me and him had different goals. I think that his goal was to raise his kids and do well. And my goal is, I want to be very successful with this business, I want to have a shop that is expanding and growing and innovating constantly. I think, for about a decade, there wasn't really a lot of system innovation. My dad's understanding of technology stopped — he's probably about 15 years behind. And so, as you can imagine, there's a lot of technology that has progressed in the last 15 years that he didn't really take advantage of, while my dad has never seen a filing cabinet that he didn't want to buy.

Pete: Over the course of the next few years, Deking maintained a split personality. One side of the shop consisted of the Acme department, which included multiple Acme screw machines that were, in some cases, more than 50 years old. The other side was the CNC Swiss-type machining side of the business, running under Jouni’s CNC expertise and David’s business management. And while the Swiss side of the shop was taking off, David continued to find other aspects of the business that were running on outdated technology. He determined that the shop was only utilizing 10 or 15% of the ERP or engineering resource planning system’s capabilities — that is, the capabilities of the software platform that helped organize operations. Rather than relying on this software, the shop was still printing and faxing quotes and dealing with requests for quotation one at a time as they came.

But the most pressing issue was with the Acme Department. Just as Covid-19 started to shut the country down, more and more work was being moved to the Swiss-type machines, and now overhead with the Acme division was holding Deking back.

David: You know, the year prior to COVID was the best year we've ever had. I would say about 80% of the revenue coming through was from the Swiss. And we were doing really well. I think because of the revenue, we weren't really too worried about things. No, we were kind of working with my dad to say, “Okay, you're going to need to have a timeline here of when we can get the Acmes profitable by. Otherwise, you know, we can't just keep going this way.” And what we agreed on was actually the end of January, so even before really COVID was an issue. And, well, January came and kind of went. It was pretty apparent that the Acmes hadn’t really turned around yet. Then, right when lockdown happened, no one knew what was going on, but I knew, “Hey, man, if you know we're having to lock down here, we can't sustain a department here. I remember he kind of drew a hard line in the sand about you know, that we weren't going to close it. That's not how exactly it went, but he drew a hard line about something like that. And it was that was kind of the final straw for me.

Brent: Just the brief amount of time in which these hugely consequential talks took place between Geno and David — not to mention the fact that they are father and son — created tension. The two DeVandry generations each thought the other was moving too fast or too slow. Predictably, the pressure came to a head. One day, David wrote a letter to Geno, stating that unless there were a few changes, he would be moving on.

David: So, it was tough. Myself and Jouni, we always wanted to pursue the Swiss route, we thought the Acme department was kind of holding us back. And meanwhile, I understood my dad's point of view. I was raised on these Acmes, these Acmes paid for my childhood, paid for me growing up. We've had employees in the Acme division that had been working with us for over 40 years, multiple employees. And I understood, if I'm talking about closing this department down, what that means for him is he's going to have to layoff employees that are family to him. There’s something to say about that, one thing I can learn from that is, there is a humanity side to business, one that might not make financial sense. And I think it's important. We need to make sure we're taking care of our employees.

One thing I can tell you about my dad for sure is he's always taking care of his employees, always, to the point where and this is the kind of quality that my dad — I love this quality about him. I also have this quality too, but I have to check it more. The fact is my dad would rather be the guy being taken advantage of than taking advantage of somebody else.

The problem is, we weren’t going to make it through and unless we made some decisions there. It got to the point where I was the one who had to call these employees that worked with us for decades and lay them off because he couldn't do it. And I understand why. It was a difficult time, as you can imagine. My dad went from going to work every day to kind of having to stay home, not really being part of the business, watching his business being transformed to something different than what he knew it to be. And I'm sure it was tough.

Geno: Well, when David started taking over, he wasn't really interested in the Acme department, which is where I had most of the people who had been with me for many years. And truthfully, that part of the business had slowed down, it wasn't as efficient financially as the Swiss department. And we were struggling with whether we should keep it going or not. We had some big orders. And then somehow, Boeing had problems and that dropped off and different things happened, and the screw machine part was not very efficient. My son kept pointing it out to me, and we had issues about that, because I just didn't want to let these people go. I kept trying to figure out ways to keep them here.

I realized accomplishing that would cost us a bunch of money, putting it into the Acme department that wasn't being very efficient. And truthfully, if I'm going to retire, who the heck is going to maintain that part of the business? Because I'm the one that understands that, I grew up in it. I think I'm really good at that business — you do it for 50 years, you got to be good at something, right? — So if I'm not going to be here, and I'm not planning to be here the rest of my life, how can I tell them to keep it open? It came down to where we really had to shut that down, and it hurt, because I had people that I seriously cared about. I told David and Jouni, “if you let these people go, you better make sure you give them a good severance.” And that's what we did. And truthfully, fortunately for us, we had the money to do that. There were times in the past we didn't have the money to give out a nice severance. So that is what we did and it hurt. Those kinds of changes hurt.

Brent: But he was giving you credit for a level of humanity — even to the point where business was slow and some of these guys really didn’t have much to do — that you still wanted to make sure they were taken care of, and that it was kind of a different viewpoint on running a business. And he really talked about that quite a bit, so it sounds like he was absolutely right about that.

Geno: It's true, I am very close to my employees, and they looked after me. I had situations where when I had to lay people off, I was really bad. They come to me and say, “You’ve got to let me go. Don't let my brother go, he needs a job, but I can do something else.” I'd hire somebody in and they'd find out something about them, and they said, “Geno, you’ve got to get rid of this person, because they're not looking after us.” I liked how they said “us.” My employees looked after me, and I looked after them.

David: To give you a little feedback on that letter. I mean, in that letter, it was all business. It was just saying, “Hey if you don't believe your Acmes aren't making money, I'm going to prove it to you.” I took numbers, and I went down went deep into numbers. I pretty much proved it with the numbers. I didn't really have objective data, but I got as objective as I could with that. I don't know if that's really what pushed him over the edge or the fact that I had to threaten to leave. But I don't think it was the numbers that did it.

Geno: Well, I remember what it was about, he basically told me, he couldn't continue the way things were going, he needed more from me. I remember saying, “Just be patient, you're trying to go too fast. It's not that I don't want you to run this place or take it over. I just want you to slow down a little bit.” We sat down and talked about it, and he agreed that he was a little bit anxious. I agreed that maybe I got to give him more room. It hurt. I want to tell you, it really hurt.

By the way, I did the same thing to my dad. I just thought about that. I remember with my father I was running, literally when I worked in the shop when I was younger, people didn't even know I was his son. He said, “When you come in here, you're an employee.” My dad told me that, he was pretty tough. And one day I told him, “You know what, I'm leaving in two weeks, you’ve got two weeks notice, I'm leaving. I'm going to get another job.”

During those two weeks, he kept talking about our future. I kept looking at him like, “I told you I'm leaving.” I didn't say that to him. I said, “You know I'm leaving.” And when it got down to the last end of the two weeks, he said, and I don't think my dad ever said this to anybody ever in his life, said, “Son, don't you know I need you here?” It's an emotional time.

Truthfully, that was the same situation with David. I needed him. I wanted the shop to keep going because, again, I look at this as like an heirloom. My dad passed it on to me, and I passed it on to him. He's got two boys, I've got other grandkids that maybe someday they'll pass it on to them. I have no idea. He's got one son, that's pretty remarkable. So we'll see. But I don't know, you look at those things and you think, how long can this go on? Three generations? Pretty tough. That's not easy to do.

Pete: Today, Deking Screw Products operates 10 CNC Swiss-type machines, the shop has become more digital, it has revamped its production flow through the ERP system and it has achieved certification for AS9100, a quality standard for aerospace-industry manufacturing. The company has been able to rehire several of the employees it laid off in recent years. It continues under David and Jouni’s leadership, with Geno coming and going to assist when he pleases.

Geno: The biggest problem we had in the beginning, was he wanted to change everything overnight. I said, “Wait, son, just take one at a time and get it done. Don't do it all at once, one at a time.” I had to remember, remind myself that when I took over from my dad, he left, he got out of the way. He let me make my mistakes. I realized I had to let him make mistakes also.

My son has done a remarkable job. I had tried several times to become ISO certified. And I got ISO certified prior to David coming in, but it wasn't done perfectly. When he came in, he not only got involved, but he understands it, he owns it. He's also got into AS9100. He's working now on two other certifications. He understands this stuff, he’ll sit down and read and get involved in those things. And I have to tell you, he really has impressed the heck out of me. It took me a while to get him to slow down and for me to trust his changes. And finally, I knew I had to get out of the way.

David: With my limited business background of a couple of years running a couple of learning centers and doing data collection, I knew we eventually had to get to the point where we had to collect some data as well. With my dad, at the end of the month, if we had money in the bank, we were good, and if we didn’t, we didn’t have a good month.

My dad's a pretty devout Christian. And I think he attributes a lot of his success, just trusting God and making sure — It kind of fell in line. To his point, he's been running this business since he was 19 years old, and he just retired, and he's in his late 60s now. He kept it afloat the whole time, even during a wait, we got down to three employees, and he kept it going. So his point, he was successful, and he also raised five kids with it.

Geno: Business in this industry seems to have cycles up and down and up and down. When you cut down from 45 people to three people, at that moment, you begin wearing a lot of different hats that you weren't wearing before. Then, all of a sudden, you’ve got to give it all back again, as you hire back. What happens sometimes, is you’ve got to let go of these things. David right now is training all these people. If everything slows up, if things slows up really bad, he may have to take on some more hats, and wear those things all over again. That's an issue that he has to be aware of, that's the kind of things I'll share with him — that it doesn't always go great. But one of the things in this business right now: they are set and ready for this next surge in business. I think we're going to see it. I'm excited about the future, I think we're going to be very busy.

We've got all the certifications in place, we’ve got people trained, they have all these people learning new jobs where he doesn't have to do everything. He's got it where he gets to plan and think about the next project: How am I going to solve this problem? He keeps working on these things, and so they're in a great position for the future.

Brent: So there you go. So many lessons to be learned from the DeVandrys’ story. I do want to say thank you, so much, to Geno and David DeVandry for sharing your stories with us. Definitely go check out their shop at DekingScrew.com. They recently overhauled their website and have a very cool virtual tour of the shop.

There’s also a written sort-of companion piece to this episode where you can see a photo of Geno and David. Just go to MMSonline.com and search for Deking Screw Products, or you can visit the Made in the USA website and we’ll link to it there. Ok, here we go:

Made in the USA is a production of Modern Machine Shop and published by Gardner Business Media. This episode was written and produced by me, Brent Donaldson, and by Peter Zelinski. I also edit the show. The series sponsor is Hardinge.

Made in the USA was recorded at the historic Herzog Studio, home of the non-profit Cincinnati USA Music Heritage Foundation. Our outro theme song is “Back Home” by The Hiders.

If you are enjoying this series, you know what to do: If you’re using Apple Podcasts tap the fifth star on the main page of the show.

I do want to give a shout-out to listener R. A. Calhoun, who said that he was getting a sore neck from nodding in agreement with this series, and that it should be required listening for decision makers and politicians and parents — and then proceeded to give us only two stars. So, that’s what happens when you mosh to a podcast, folks.

If you have comments or questions, email us at madeintheusa@gardnerweb.com. Or check us out at mmsonline.com/madeintheusapodcast.

For the next episode, we’re going to wrap all of this up. Our series finale will be a look into the possible for U.S. manufacturing: what’s possible now to strengthen it, what are its prospects and what can we do to strengthen those in the future. “The Way Forward,” next time on Made in the USA.

RELATED CONTENT

-

Cenit Elects New CEO as Former Leader Resigns

Peter Schneck will assume the role of CEO on January 1, 2022. Kurt Bengel, the outgoing CEO, will resign his position on December 31, 2021 and leave the company after more than 33 years with Cenit.

-

RobbJack Corporation Names New President

Over his 26 years at RobbJack, Michael MacArthur has developed a reputation for building relationships and providing innovative solutions to meet customer challenges.

-

Stars Slowly Align for Small Shop Merger

RPM Tool’s seemingly overnight expansion from a five-person machine shop to an almost 30-employee production business involved over a year and a half of planning.

.1692800306885.png)

.1687801407690.png)